The COVID-19 pandemic is bringing fundamental challenges to the cultural sector around the world and forcing hard decisions about programs, staffing, and public safety. At a moment when it is difficult to forecast the next ten days precisely, it might seem slightly absurd to think about a ten-year horizon. It is worth the effort – wiser investment of time and resources is made with a lens tilted toward the future. Below are six factors that should probably inform intelligent decision making.

1) Focusing support for artists, creators, and makers

Most of the artists and creators who are directly crafting the events that bring people together are “gig workers” moving from show to show to find the next paycheck. They do this largely without the benefit of labor protections, and without any significant savings to draw on in times of crisis. As the economy restructures following this crisis, the means to provide appropriate support for them needs to be addressed, with part-time and freelance workers granted similar protections as their full-time institutional colleagues. They deserve a better backstop than GoFundMe.

This work – no doubt requiring sustained advocacy – aligns with the broader labor movement that is now finding purchase, especially with younger demographics, after several decades in retreat. Some boards that foresee an associated higher wage bill may resist, especially those that bring their corporate instincts to bear. But failing these critical workers undermines the mission that lies at the heart of institutional success. (Building more representative boards or developing a governance model that also seeks input from worker, community, and other advisory councils may help find a way through this dilemma.)

2) Rethinking opportunities for public investment in the sector

Cultural organizations in the United States lobbied for a $4 billion allocation from a $2 trillion stimulus package; while the situation is developing, early reporting indicates they will come away with about $200 million. Meanwhile, the American Alliance of Museums calculates museums are losing $33 million per day due to closure – so this federal funding would have been exhausted covering losses at museums alone just one week into the ongoing crisis.

Relying on the U.S. government for funding has rarely been a winning strategy for the arts, and attention will now turn to state and local governments to marshal the level of resources required to weather this storm. If closures mount, some will suggest cultural organizations were irresponsibly capitalized, with the median U.S. arts organization holding under two months of working capital. However, this is a Darwinian viewpoint that struggles to align with the reality of the not-for-profit business model, which typically only creates net assets by attracting contributed income (indeed, there is literally no such thing as “retained earnings” in not-for-profit accounting). Yet many philanthropists suggest their contributions could be better deployed than by bulking up a balance sheet: either in providing mission-related programs and services now, or through long-term investments with more potential impact than cash reserves.

Could there be a planned role for government support during times of significant disruption? We should not forget that not-for-profit institutions are made up of people, most of whom are paid lower salaries than for equivalent work in the for-profit sector. Staff often take that cut with open eyes knowing that they are providing valuable services to society – services that reflect and support that which makes us human – but the sector’s thin capitalization means they are at higher risk when crisis hits. Denmark might have an interesting idea on this front: perhaps 80% wages paid for laid-off / furloughed workers for up to 12 months, up to 150% of the average annual wage in the area – or fill in the largest percentages / durations you can advocate for with a straight face. Governments could also flex tax rules to spur donations to cultural institutions. With federal tax filing deadlines now delayed, could private fundraising be increased by extending the deadline for donations reflecting the 2019 tax year, when many people will have had significant gains?

3) Dealing with the climate crisis

Pre-pandemic, I would have said that the climate crisis was the existential question of the decade ahead – and it may still be. Ten years ago, CO2 levels were at 391ppm; the latest measurement is 415ppm – even with more than two months of large-scale shutdown in China – and we are continuing to approach the 450ppm level that most scientists consider a critical threshold to keep global temperatures under control.

Arts and culture may be far from the worst offender, but there is low-hanging fruit to be found – and now some time to think about how to break past cycles. With travel suspended, will we find an alternative to a carbon-spewing international flight to the next biennial? With public closures and engineers and maintenance workers on limited duty, can we find efficiencies in how we build and operate “always-on” buildings? While it may be challenging for cultural institutions, artists, and other individuals to drive the society-level changes required to address our planet’s climate, the sector can be advocates and leaders on this issue.

4) Navigating the continued evolution of the attention economy

The competitive waters for culture have been heating since the early 2000s. Since then, cultural institutions have become, in many ways, visitor attractions, responding to patrons who now have many more options for their time and focus – 500 channels of cable television, an iPhone in your pocket, and the nearly unlimited choices provided by Amazon, Netflix, YouTube, and Spotify. Culture is no longer limited to art or music; younger audiences, COVID or not, see food, cocktails, fashion, and more as equally indispensable cultural pursuits worthy of engagement. Even as “stay at home” orders have eliminated commuting time, we have still more than filled our 24 hours each day. (I will not attempt a list of ‘Peak TV’ shows I will never get to watch.)

Cultural organizations will need to think creatively to find a position that can respond to demand, navigating between the dynamic growth of advancing technologies and a human-scale connection. Will COVID-19 tip us toward a longer-term digital reliance, leveraged further by new business models that create exponential opportunities once they reach scale? If so, how can issues around privacy be focused such that choice and humanity be prioritized? Or, after binging on Netflix for weeks – or months – will there be a thirst for personal, live encounters with artists and content (perhaps, in small groups, at a safe distance)? What are opportunities for close collaboration between curation, interpretation, and experiential design to reconnect audiences to unique understandings of culture and the people around us that it represents?

5) Building the future of infrastructure

The focus on online programs during the quarantine will likely move digital infrastructure up the priority list – but we should also ask how we will regather as people on the other side of the virus. While our current need to disconnect may be of a larger scale that those alive remember, humans have always returned to the social sphere following fear-generating pandemics and wars of the past. Semi-pixelated Zoom happy hours will only meet our social needs for so long.

Over the last decade, many parks and libraries had effectively reimagined their identities as public space. Can organizations centered on arts, history, and sciences find similar opportunities to create a place for encounter and engagement with people not quite like you? How might these organizations respond to a push for smaller-scaled spaces, with more focus on informal engagement among fewer people? The core values of the sector are buoyed by openness, and its buildings and spaces should devote attention to creating opportunities for connection to all people.

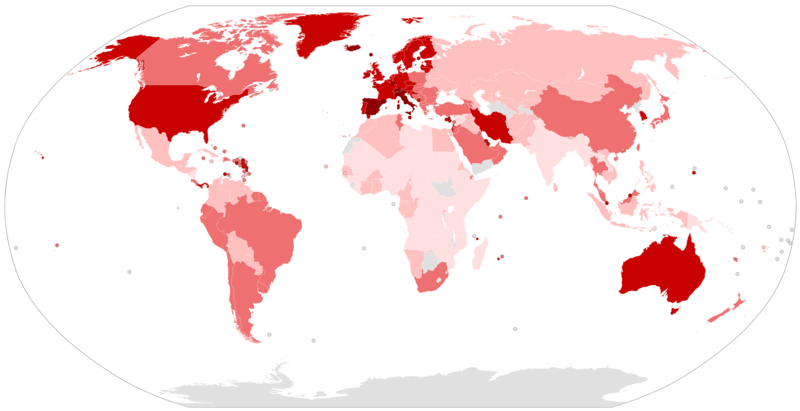

6) Learning from the global experience

What can the cultural sector in the west learn from the lessons of China, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and others in Asia, both in terms of how they responded after SARS and as they begin to reopen now? How can lessons from their experiences be distributed quickly around the globe, forming the basis of scenario planning and more structured decision making about the possible paths forward? This is also potentially an opportunity to build more networked, "full-service" not-for-profit organizations – either across geographies or even across disciplines.

If the forward agenda for the sector was worth focusing on two months ago, it is doubly so now: local community building, climate-sensitive practice, digital programs that protect privacy, deeper engagement with our fellow citizens. Your list may vary – but thoughtful planning can find arts & culture leading on the other side of this crisis.